Last year it was the Autonomous Region of Tibet; this year it is the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. China, it seems, is undergoing another round of its periodic socio-political upheavals.

Chinese history is not customarily taught in America, so many are unaware of the regular regime changes that have taken place in China during just the past 1,000 years. These changes were not only political, but broadly cultural and religious, and they affected uncountable millions of people in this densely populated part of Asia.

Most of us are familiar with the communist take-over of China in 1949. This event is often viewed simply as the spread of communism during the 20th Century, and too infrequently viewed from the perspective of 1,000 years of Chinese political maneuvering. The communist period is but a brief blip in China’s long history, a dramatic but short interlude in an otherwise multi-millennial exploration of social organization. Accordingly, the relationship, role and responsibility of the individual to the state have undergone myriad revisions.

As is true in the West, China’s political system has been inextricably bound to religious institutions, or in the case of the communists, anti-religious institutions. These institutions – whether Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian or atheist – garnered the allegiance of many millions of people and thereby exercised social and economic influence. Over the last 1,000 years, successive Chinese Dynasties and regimes overtly and covertly played politics with religion, aligning or disassociating itself from such institutions depending upon economic and military implications. Alternately promoted or suppressed, the leaders within China’s major religious faiths oscillated between being valued advisors to emperors or labeled “parasites” and disenfranchised outcasts. The Falun-Gong movement, embraced in 1992 by Chinese authorities was then accused in 1999 of “promoting theism and jeopardizing social stability;” the communist party persecuted Falun-Gong members and its practices were banned.

An equally powerful vein within Chinese culture is its devotion to an organized civil service. Historically, the bureaucratic legions of state supported workers were part of a highly-regulated society which included rigorous education and examinations for civic officials. While lending stability to the apparatus of government, this highly-regimented mode of social organization continues to strongly resonate through Chinese culture, and can clearly be observed in the hegemonic control of the Communist Party in China today.

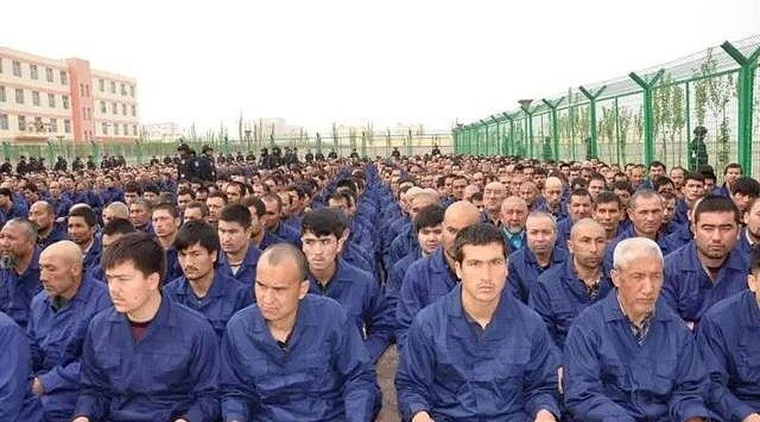

China’s absolute insistence that both Tibet and the Uyghur regions are historically part of China proper is based upon the various political, religious and economic alliances that were formed and dissolved during the past millennia. The Uyghur region in western China, for example, largely populated by Turkish Moslems, was once controlled by the Mongol Empire, 1206-1368 A.D., as was China as a whole. It was under the protection of the Mongols that Tibet established its Lamaist governmental system; the first Dalai Lama was appointed by the Mongols. The point is that for varying lengths of time, vast areas of what we today call China were in fact wholly autonomous countries or under the control of various other Empires.

In Europe, the countries cobbled together by the English, French, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and other empires have fractured. The same is true for the former Soviet Union. As the information age extends, despite its great age and military efforts to the contrary, it is reasonable to expect China will undergo a similar deconstruction in the years to come.